The Battle Of The Strait of Otranto 1917

Added on 06 August 2017

The East Neuk Lads and the Battle of the Strait of Otranto 1917

I sometimes wonder if my grandfather George Watson ever met the Austrian artist Egon Schiele as he stood guard and sometimes drew Russian prisoners of war in Prague in 1917. You never know! According to his Royal Navy Service record George enlisted in October 1915 stating his age was 18 years 2 months. This wasn’t entirely true as he had just turned 17 years 1 month precisely. Much to his parents displeasure he had gone with his pals to sign up at Leven with the promise of a smart uniform that was sure to impress the girls and the chance to see a bit of the world. George was then sent to HMS Columbine a berthed training vessel based at Port Edgar where he received basic training in mine laying and boom defence work.

I sometimes wonder if my grandfather George Watson ever met the Austrian artist Egon Schiele as he stood guard and sometimes drew Russian prisoners of war in Prague in 1917. You never know! According to his Royal Navy Service record George enlisted in October 1915 stating his age was 18 years 2 months. This wasn’t entirely true as he had just turned 17 years 1 month precisely. Much to his parents displeasure he had gone with his pals to sign up at Leven with the promise of a smart uniform that was sure to impress the girls and the chance to see a bit of the world. George was then sent to HMS Columbine a berthed training vessel based at Port Edgar where he received basic training in mine laying and boom defence work.

The Royal Navy valued the skills fishermen already had before they enlisted. As fishing became a restricted occupation during WW1 and most of the countries fishing boat fleet was requisitioned by the Navy George found himself going to war in the same boats he had made his living on just a few months previously only there was a small fixed gun at the bow and fishing nets were replaced with larger wire mesh nets and buoys designed to detect submarines.

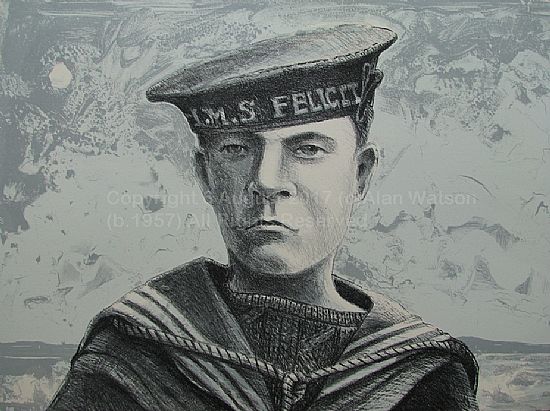

In the early summer of 1917 George was a deckhand on HMS Felicitas, a converted drifter formerly registered in Buckie. HMS Felicitas was a small part of a huge number of drifter boats which manned a 45 mile net barrage laid by the Allies between Brindisi in Italy and Corfu in Greece which was intended to deter the Austro-Hungarian Navy from entering the Mediterranean and threatening allied shipping there.

Because of the demands of the Gallipoli campaign the barrage which was begun in 1915 was never entirely effective as there were not enough allied ships to man it effectively the system being called a large sieve through which U boats could pass with impunity.

In 1915 and 1916 there were a number of raids mounted by the Austro-Hungarian Navy against the barrage however the largest and most dramatic occurred early in the morning of 15th May 1917.

During a short naval engagement three Austrian destroyers and two cruisers sank fourteen allied drifters, HMS: Admirable, Avondale, Coral Haven, Craignoon, Felicitas, Girl Gracie, Girl Rose, Helenora, Quarry Knowe, Selby, Serene, Taits, Transit and Young Linnett.

Along with most of his crew mates George was picked up by an Austrian cruiser and taken to the Port of Cattero.

From this point accounts of what happened next vary as the Austrians split up naval officers from basic ratings. George certainly talked about going on a three day journey to Graz by cattle truck, locked up in a fortress in the middle of the city for several days, then walking in his bare feet through Prague and marching past Russian prisoners of war for 24 hours. He noticed they only had one boot for every hundred men. This sight made quite an impression on him. When he was an old man he told me he had great admiration for the Russian people. He thought they really pulled up their boot straps from the time he saw so many of them in 1917 to then become the first nation to put a man into space 50 years later.

At this time when I asked him if he ever tried to escape he roared and laughed telling me that at one place he was imprisoned the fort was surrounded by a dry moat. The building was so well fortified they only needed one perimeter guard as nobody had escaped from there since it had been built a century before. This may have been Terezin which was used to house Allied Prisoners of War in World War One. In World War Two it acquired a much more sinister reputation when it housed displaced Jews on their way to the death camps of Western Poland.

George eventually ended up interned in the Prisoner of War camp at Deutsch-Gabel in Western Bohemia close to the German and Polish border. This camp held two thousand Russians, four French submarine crews and around fifty seamen from the East Coast of Scotland. Until Red Cross parcels started arriving Grandad and his pals existed on a starvation diet of sauerkraut and black bread. They had to swap all their uniforms for Austrian clothing which was not as warm as their uniforms.

Deutsch-Gabel is now called Jablonné v PodještÄ›dí. It is surrounded by high mountains and alpine style scenery. George told me that when they complained about their lot to the guards they were told “Relax and enjoy this place! If you come on holiday here in peacetime you couldn’t afford it!”

On 1st September 1918 in a postcard home to his uncle he wrote “I wish I saw the war over. I am getting fed up of this life (prisoners) now. We are all in good health at present, hoping you are the same.”

After 18 months of constant hunger, occasionally eating rats and raw grain from the fields, the war was over. As the countries in Eastern Europe descended into bitter civil wars following the collapse of imperial power George and his pals managed to make their way south by train or horse and cart through Trieste, then Venice before reaching France.

George eventually arrived back at Pittenweem train station on a Sunday in 1919 where he was met by his parents and a nephew. He was covered in scurvy sores which took a long time to heal.

When I was a little boy I enjoyed looking at my grandfather’s World War One medals which hung in a frame in the sitting room and looking through his volumes of A History of the Great World War which sat on the bookcase and told him of all the events he had missed while a Prisoner of War.

In many ways the First World War hastened the demise of the Scottish fishing industry which was my grandparents living. Despite his harrowing experience of captivity in World War One I think my grandfather enjoyed his time in the Senior Service. When World War Two came he volunteered again and as a boom defence boat skipper with the ‘Wavy Navy’ went on to have many more adventures in the North Atlantic and Mediterranean.

Sources

- First hand accounts from George Watson

- Watson family correspondence, family records and memories.

- The National Archives.

- ‘Otranto Boom, Report on the Raid by the Austrian Navy on the R.N. Drifters operating the Otranto Boom Defence in the Adriatic Sea’ by Skipper George McKay of MacDuff, H.M.Drifter ‘Helenora’. From Portsoy Past and Present.

- ‘The Naval Battle of Otranto’, Part 6 from ‘The Annotated Memoirs of Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya, Regent of Hungary’, at Don Mabry’s ‘Historical Text Archive’ http://www.historicaltextarchive.com/books.php?action=nextchapter&bid=9&cid=6 accessed 25 April 2008, 20 April 2017.

- ‘Memories of a War-Time Sailor’ by J.M.Smith, East Fife Mail, Wednesday August 30th 1967 for 6 weeks.* George Watson is mentioned along with James Aitken of St Monance in ‘Part Three: Two Tins of Meat Our Key to Freedom.’ Grateful thanks to the Archivist Gary Nurse, Friends of Methil Heritage Centre, who kindly sourced the articles for me in May 2013.

*Alison Humphries has recently compiled an edition of 'Memories of a First World War Sailor' by John M Smith, along with research notes, and family history. This interesting and informative publication is available from the Scottish Fisheries Museum, Anstruther, which held a Battle of Otranto exhibition throughout May & June 2017, East Neuk Books & Giftware, Rodger Street, Anstruther, Crail Museum & Heritage Centre, Marketgate, Crail. Also Amazon (£5.99 paperback, £2.99 Kindle). ISBN: 978-1546426912. All proceeds will go to RNLI, Anstruther Lifeboat Station.

Footnote

If you happen to have any information about how the lads got home, which I hear is a rip roaring story, I'd be glad to hear from you. Please leave contact details on the form below and I'll get back to you shortly (the comments are moderated and I won't publish anyone's contact details). My grandad told me lots about how he ended up at Deutsch-Gabel but as for coming home he was just glad to be back!

The feature at St Andrews Citizen Friday May 26 2017** mentions that I contributed information about David Watson for the Scottish Fisheries Museum commemorative centenary exhibition. The material I contributed for the exhibition was about George Watson and the 'Felicitas' not David Watson. That said George's second cousin David Watson (the son of 'Star Jeems' born in 1871 - not to be confused with 'Auld Star Jeems' born 1802 who married Margaret Reid) was also at the Battle of the Strait of Otranto, where he was the skipper of the 'Morning Star'. The boat and crew of the 'Morning Star' survived the battle.

**"Marking the Centenary of the Battle of Otranto - The role of East Neuk boats in key sea battle during First World War', by Debbie Clark, St Andrews Citizen Friday May 26 2017, p6-7.

Further information

My painting of George Watson (left) is one of three portraits of my grandfathers titled Ancestral Tryptych and can be viewed at the Scottish Fisheries Museum from time to time. If you are travelling any distance to view Ancestral Tryptych please contact the curator at the Scottish Fisheries Museum ahead of your visit as they may be able to arrange for you to view the paintings even if they are not currently on display.

My painting of George Watson (left) is one of three portraits of my grandfathers titled Ancestral Tryptych and can be viewed at the Scottish Fisheries Museum from time to time. If you are travelling any distance to view Ancestral Tryptych please contact the curator at the Scottish Fisheries Museum ahead of your visit as they may be able to arrange for you to view the paintings even if they are not currently on display.

New Print

'Deckhand' Copyright (c)2017 Alan Watson All Rights Reserved

Lithograph and Screenprint, the image is of a young naval 'Deckhand' at the Battle of the Strait of Otranto, 1917. A limited edition of 10.

Contributed: 06/08/2017, 15:00:00

Original post Copyright 24 April 2017 (c)Alan Watson (b.1957) All Rights Reserved

Updated post Copyright 6 August 2017 (c) Alan Watson (b.1957) All Rights Reserved